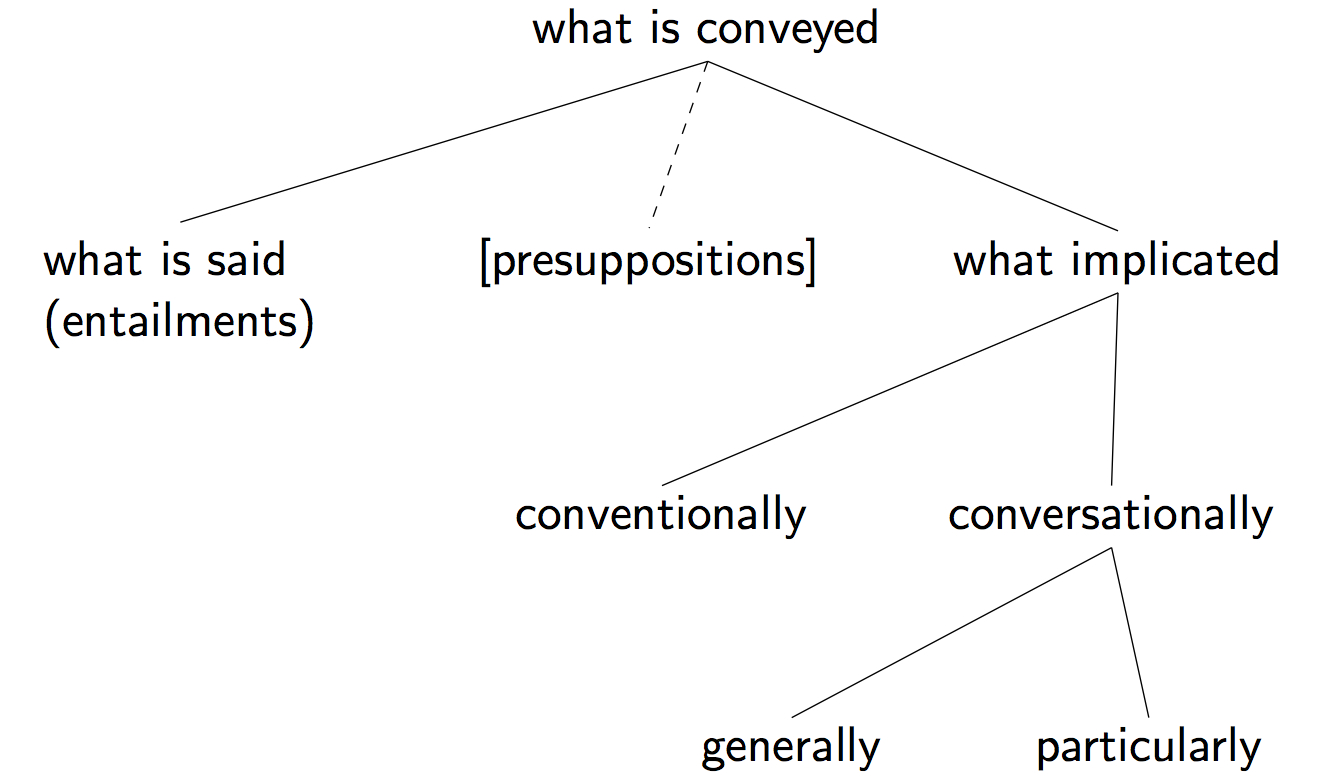

The study of Pragmatics focuses on

meaning that is conveyed beyond what is stated overtly. The taxonomy

below divides "what is conveyed" into 2 main types of meaning: what is said

and what is implicated. The former corresponds to entailed propositions, and

in terms of use, it's what a speaker is on record as having said or committed

themselves to. The latter corresponds to propositions that represent

additional meaning, beyond what is on the record. You can see that there is a

third intermediate type of proposition that is relevant to what is conveyed; these are presuppositions, which are not so much part of what is conveyed as a prerequisite for evaluating what is said. On the scale from semantic meaning

(entailment) to pragmatic meaning (implicature), presuppositions lie in between.

In the preceding pages, we've been discussing conversational implicatures. This taxonomy reveals a further distinction between particularized conversational implicatures and generalized conversational implicatures. Here's the distinction:

Particularized conversational implicatures arise only in special contexts. For example, uttering the sentence in (34) does not normally implicate (35).

(34) Mary went to Los Angeles and San Diego.

(35) Mary did not go to San Francisco.

However, when (34) is embedded in a context like (36), the list of cities is taken to be exhaustive when it's the answer to Speaker A's question. In (36), therefore, the additional meaning of (35) that Mary did not go to San Francisco IS implicated. This is a particularized conversational implicature because it took a particular context for it to emerge.

(36) A: Which California cities did Mary visit?

B: Mary went to Los Angeles and San Diego.

On the other hand, generalized conversational implicatures only go away in special contexts, i.e., they apply generally. For example the use of the indefinite "a house" in (37) implicates (38), and that implicature arises without any extra special context to bring it out.

(37) Joe staggered into a house and fell asleep.

(38) Joe staggered into a house that was not his own house.

(39) Joe staggered into a house and fell asleep. When he woke up, he realized that he was at home.

It's possible to make the implicated meaning of (38) go away, as shown in (39), but, as you can see, it is a special discourse context like (39) that is needed to provide a way to make the generalized conversational implicature go away.

Lastly, in the taxonomy above, there is another kind of implicature listed: Conventional implicature. These are so named because some inferences have become stuck to certain 'host' expressions. These kinds of implicatures have the following properties:

An example of an utterance that gives rise to a conventional implicature is (40), with the host expression 'even'.

(40) Even Bill came to the party.

The implicature is not calculated via the maxims; it arises in all contexts where 'even' is used, regardless of the preceding question, and you can see in (41) that cancelling the implicature is awkward ("#" marks expressions that are grammatical but infelicitous).

(41) Even Bill came to the party # but Bill always comes to parties.

KEY POINT: Implicated meaning can be classified as conventional implicature or conversational implicature, and conversational implicature can in turn be divided into particularized and generalized implicatures.

Grice, H. P. (1975) Logic and conversation. In P. Cole & J. Morgan (Eds.), Syntax and Semantics. Vol. 3. New York: Academic Press. pp. 41-58.

Content adapted from S. Kaufmann (2008) teaching materials, Northwestern University.