Linguistics has a bunch of well known examples that are trotted out as reminders of the tricky cases that any viable model of a given phenomena must account for. One such case is the Winograd example in (14), in which the referent of "they" switches from "the city council" in (14a) to "the demonstrators" in (14b) without any structural changes in the positions of the pronouns or their antecedents.

(14) The city council denied the demonstrators a permit...

a. ... because they feared violence.

b. ... because they advocated violence.

Examples like (14) have been taken as evidence that pronoun interpretation can better be understood as a side effect of the more general pragmatic inferencing that is required to establish a coherent discourse. Under that approach, the patterns observed in the previous section which had been labelled the subjecthood constraint and the parallelism constraint are taken to fall out from other processes of establishing discourse coherence. This alternative approach focuses particularly on the inferences that are required to infer how adjacent sentences relate to each other. These relationship ("coherence relations") must be inferred in order for a discourse to make sense and they rely on reasoning about how particular events and situations and ideas connect. Examples (11-12) and (13-14) are repeated here as (15-18).

(15) John kicked Bill. Mary told him to go home.

(16) Bill was kicked by John. Mary told him to go home.

(17) John kicked Bill in the leg. Mary punched him in the arm.

(18) John kicked Bill in the leg. He punched Mary in the arm.

Under a coherence-driven account (Kehler 2002), an observation that has been made regarding cases in which apparent subjecthood biases emerge is that such cases often involve narration relations -- i.e., pairs of sentences in which the second sentence answers the question "what next?" relative to the first and could be signaled with the connective "then" (15-16). A related observation is that the apparent parallelism bias emerges most strongly in cases in which the relation itself is highlighting parallel elements across two sentences -- i.e., pairs of sentences in which the second sentence answers the question "what's similar?" relative to the first and could be signaled with the connective "similarly" (17-18). The contexts that appear to be most sensitive to plausibility constraints are those where causality plays a role -- e.g., pairs of sentences in which the second sentence answers the question "why?" relative to the first and could be signaled with the connective "because" (14).

The rest of this section on semantic constraints focuses on examples of coherence-driven biases that stem from the semantics of the verb in a sentence. The two case studies involve implicit causality verbs and transfer of possession verbs. Both verb classes have received a lot of attention in the literature given their influence on co-reference biases. A coherence-driven account helps bring together their otherwise disparate behavior.

The implicit causality (IC) verbs in (19) and (20) are notable in that they are connected in interesting ways with coreference and causal reasoning. In (19), the ambiguous pronoun "he" is easily taken to corefer with "John" whereas in (20), the structure of the sentence is the same but the preferred referent for "he" is now "Bill". This difference is driven by the verbs "amaze" and "admire". "Amaze" is part of a class of so-called subject-biased IC verbs (e.g., "amaze", "frighten", "impress", etc.), whereas "admire" is part of the class of object-biased IC verbs (e.g., "admire", "congratulate", "detest", etc.).

(19) John amazed Bill because he could stand on his head.

(20) John admired Bill because he could stand on his head.

The coreference biases introduced by these verbs have often been cast as thematic role biases whereby the stimulus referent (John in (19), Bill in (20)) but one can ask whether they would be better understood in terms of deeper semantic reasoning. In support of such an idea, note that the subject/object bias of these verbs is not uniform; in fact, the same verb "amaze" seems to be subject-biased in (21) but object-biased in (22).

(21) John amazed Bill. He could stand on his head.

(22) John amazed Bill. He clapped his hands in awe.

Another verb class that has been highlighted for what appear to be thematic role biases is the class of transfer of possession verbs as in (23). In (23), the verb handed has a Source thematic role which appears in subject position and a Goal thematic role which appears as the object of a prepositional phrase. A variety of studies (e.g., Stevenson, Crawley, & Kleinman 1994) have used story continuation tasks where participants are asked to read a context sentence and then write the next sentence of the story at the prompt. In (23), the prompt includes an ambiguous pronoun and so the participants' continuations reveal how the pronoun is preferentially interpreted.

(23) John handed a book to Bob. He ...

Story continuations following (23) can either use the pronoun "He" to refer back to John (as in "He told Bill to read it") or to Bill (as in "He thanked John"). Results show a roughly 50/50 split between Goal continuations and Source continuations. This is surprising given the subjecthood preference and the parallelism preference.

Two explanations were posited to account for this surprising salience of the Goal. The first is a thematic role preference that ranks Goals above Sources -- maybe Goals simply make better antecedents than Sources. The second explanation is an event structure bias -- a bias to focus on the end state of an event. In the context of a transfer of possession event, it is the Goal referent who is associated with the end state of the event. How to tease these apart? Well, consider the examples in (24) and (25) which vary the aspect of the verb (Rohde, Kehler, Elman, 2006).

(24) JohnSource handed a book to BobGoal. He ....

(25) JohnSource was handing a book to BobGoal. He ....

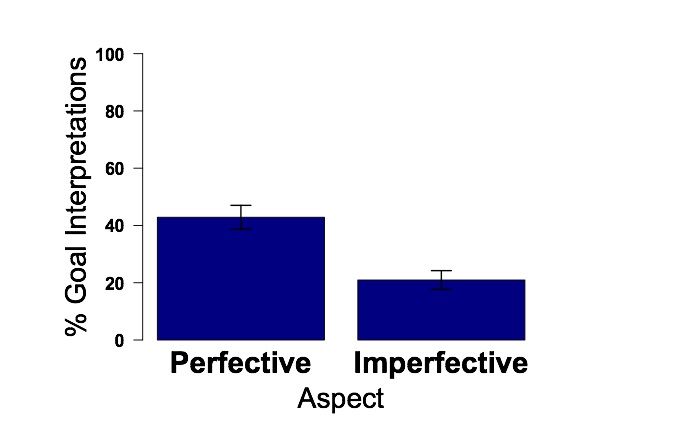

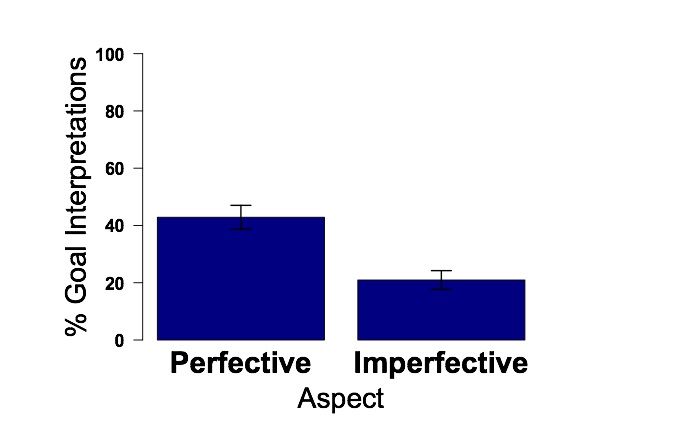

The thematic roles remain the same in (24-25) but the perfective verb in (24) describes a completed event which is compatible with end-state focus, whereas the imperfective verb in (25) describes an event that is an ongoing process, making it incompatible with end-state focus. Thus the thematic role preference predicts a Goal bias for both (24) and (25), whereas the event structure hypothesis predicts fewer Goal interpretations for the imperfective.

The results of a story continuation experiment using stimuli like (24-25) are shown in the figure below. The y-axis shows the percentage of Goal continuations. As predicted by the event structure hypothesis, there's a drop in the number of Goal continuations following the imperfective context sentences. As such, the surprising salience of the Goal appears to be a side effect of event structure.

However, one can then ask a further question of whether the event structure bias is itself a side effect of something else -- namely the process of establishing a coherent discourse. To explore that, the continuations elicited with prompts like (24-25) were annotated for the coherence relation that held between the context sentence and the continuation. Examples (26-31) show the six most common coherence relations that were identified in the participants' continuations. You can see how the interpretation of "He" varies depending on the reasoning that is applied to link the context sentence to the content of the continuation.

(26) John handed a book to Bob. He didn't want David to starve. [Explanation]

(27) John handed a book to Bob. He said thanks to John. [Result]

(28) John handed a book to Bob. He wanted it back though. [Violated-Expectation]

(29) John handed a book to Bob. He passed him an apple too. [Parallel]

(30) John handed a book to Bob. He did so carefully. [Elaboration]

(31) John handed a book to Bob. He ate it up. [Occasion]

Full definitions for each of these relations aren't provided here (though we will re-visit this when we talk about discourse coherence) but for now consider the definition of the Occasion relations (the narration ones that describe sequences of events:

Occasion: Infer the initial state of the event described in sentence2 to be the final state of the event described in sentence1.

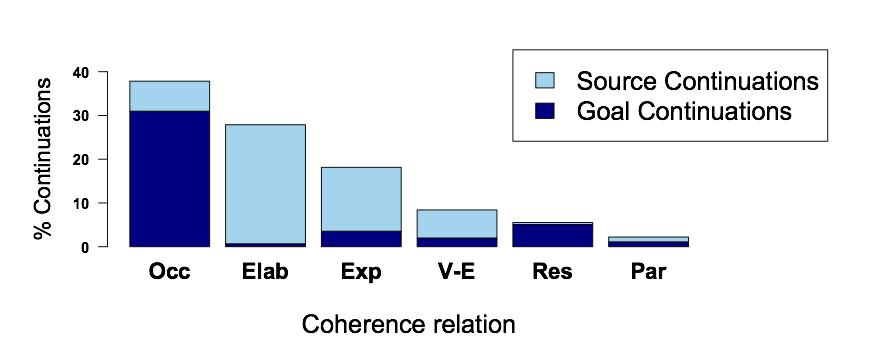

This definition makes explicit mention of end states, yielding a prediction that maybe the Goal preference that arises because of event structural biases can be localised to the coherence relation that makes direct reference to end states. Perhaps the Goal bias can be localised to Occasion relations. The figure below shows the coherence and coreference results, specifically for the perfective context sentences which are the ones that have a salient end state. The height of each bar indicates the percentage of continuations in which a particular coherence relation was operative (Occasion relations were most frequent), and the dark-vs-light blue shading within each bar shows what proportion of the continuations of that type were Source continuations versus Goal continuations (Occasion relations were dominated by references to the Goal).

What's interesting about this figure is that it shows that the Goal bias is evidence in Occasion relations (as predicted) but that a Source bias emerges in other relations like Elaborations, Explanations, and Violated-Expectations (relations that perhaps have more to do with the start state of an event). Result relations are also Goal biased which wasn't specifically predicted, but makes sense in that Results often describe a subsequent event that is causally linked to the previous event, and Parallel were simply very rare. This analysis of coherence relations shows that the event structure bias is better understood as a side effect of the process of establishing discourse coherence. Such an approach brings reference squarely in line with other discourse-level pragmatic phenomena: it is sensitive to lexical and syntactic cues but its sensitivity is driven by meaning not simply surface form.

Gordon, P.C., Grosz, B.J., & Gilliom, L.A. (1993). Pronouns, names, and the centering of attention in discourse. Cognitive Science, 17, 311-347.

Grosz, B. J., A. K. Joshi & S. Weinstein. 1995. Centering: A framework for modeling the local coherence of discourse. Computational Linguistics 21. 203–225.

Kehler, A. 2002. Coherence, reference, and the theory of grammar. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.

Rohde, H., A. Kehler & J. Elman. 2006. Event structure and discourse coherence biases in pronoun interpretation. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. Vancouver, July 26-29, 2006.

Stevenson, R., R. Crawley & D. Kleinman. 1994. Thematic roles, focusing and the representation of events. Language and Cognitive Processes 9. 519–548.