One of the big puzzles that arises in analysing language in context is why speakers choose one way to say something over another. Why do they pick a particular construction rather than some other way of formulating their message? For example, there are many ways of conveying the information that a person named Hannah used the microwave recently. Among those options, the formulation in (1) is particularly well-suited for certain contexts but not others.

(1) The last person to use the microwave was Hannah.

The part of an utterance that relates to the purpose of the discourse and anchors the content to the context is called the Theme. It indicates what the utterance is about, the topic that the speaker means to address. It may also restrict the context to particular type(s) of situation(s). On the other hand, the Rheme is the part of the utterance which advances the discourse, i.e., adds or modifies some information (i.e., the informative part). The Rheme is what the speaker says about the Theme. The Rheme is semantically predicated over the Theme. The Theme/Rheme division is sometimes termed Topic/Comment or Topic/Focus.

The domain of information structure (IS) pertains to the partitioning of sentences into categories of old and new information (theme and rheme, topic and focus). In (2) below, one can understand the fact that Horace tells jokes to be old information, whereas the newsworthy contribution the speaker makes is to say that those jokes are awful.

(2) The jokes Horace tells are awful.

In each of the statements below, the first underlined component represents the Theme/Topic, whereas the second contributes the Rheme/Focus.

(3) What I like about Linguistics is that it's full of interesting puzzles.

(4) Speaking of Linguistics, it's full of interesting puzzles.

(5) Speaking of interesting puzzles, Linguistics is full of them.

In (3), the question under discussion is made explicit via the "What I like about Linguistics" phrasing. In (4-5), the relevant questions under discussion are more general like "What about linguistics" or "What about interesting puzzles". These examples highlight how the order of information is linked to the status of information in the discourse. In producing an utterance, speakers can pick up a topical question from the preceding context and use that as the jumping off point to contribute new information. In this way, information status influences the order in which it appears: Old information (topical material) typically precedes new information. When a language provides multiple ways of expressing the same idea, speakers favor those that allow this old-before-new pattern.

The categories of theme/rheme (topic/comment old/new, topic/focus) can be difficult to distinguish. Noun phrases sometimes signal the information status of their referent via definiteness. To take an example like (6), different referring expressions are used when the entity they refer to has different information status.

(6) I saw a cat. The cat was black. Its tail was long.

An indefinite noun phrase like "a cat" requires that the discourse has not yet at that point introduced this entity. The definite noun phrase "the cat" requires that the cat entity already be instantiated in the addressee's mental model, that it be familiar and uniquely identifiable. The entity must exist either in the addressee's model of the discourse (of the referents that have been mentioned) or, barring that, in their model of the world. This is where the speaker depends on their estimate of what information is in the Common Ground. Uttering "its tail" requires that the entity itself or a licensing entity in the context ('the cat' licenses a subsequent reference to 'tail') already be instantiated. The status of the cat entity when it is referred to as "a cat" is new; when it is referred to as "the cat", the speaker is treating it as old; the entity described by "its tail" is inferable.

There are other cues to keep an eye out for. Indefinite determiners ('a'/'some') signal new. The definite determiner ('the') signals old, though there are exceptions of course (e.g. transportation: "I took the bus today"). Other markers of definite noun phrases (signaling old) include demonstratives ('this', 'that'), possessives ('my house', 'her work'), personal pronouns ('I', 'you', 'they'), and proper names ('Sandy', 'Bill', 'Italy', 'Fluffy').

The status of information as old or new is further specified by whether it is old/new for the discourse or old/new for the hearer. Information is discourse old if it has been explicitly introduced into the discourse (by language). Also some highly salient events, entities, etc., are included, which can count as discourse-old once they have happened or appeared. Information is hearer old if it is known to the hearer from prior experience (huge amount of such information). This information includes all kinds of assumptions about linguistic conventions, social norms, real-world events, general goals. Information is discourse new if, at the point at which it is offered, it has not appeared in the discourse before. Information is hearer new at its first reference in the hearer's experience.

Indefinites are often discourse-new/hearer-new. Definites and non-demonstrative pronouns (it, he) are often discourse-old/hearer-old. Inferables are technically Hearer-new/Discourse-new but they pattern with old information in using the definite determiner. Inferables are typically treated as OLD since they pattern with old information. They depend on knowledge assumed to be Hearer-old & the presence of a trigger in the preceding discourse.

Diagnosing the information status of the entities mentioned in a sentence and the information structure of that sentence depends on context: It depends on what information is topical and given at that point in the discourse; it depends on what information the speaker takes to be in the Common Ground. Consider a context with little Common Ground between speaker and hearer. The statement in (7) would be a reasonable way of expressing an answer to a (potentially implicit) question about what happened.

[Context: neutral question like 'What happened?']

(7) A dog chased a cat.

In a context where the (implicit or explicit) question is one about either the chaser or the chasee, the same response in (7) can be intoned differently to signal what piece of the answer contains the new information. New information is focus-marked, meaning that the target word receives accent placement or stress, higher pitch, and louder amplitude, as indicated with the all-caps in (8-9)

[Context: 'What did the dog chase?']

(8) The dog chased A CAT.

[Context: 'What chased the cat?']

(9) A DOG chased the cat.

These examples show how intonation is linked to information structure. Note that all the variants are grammatical; it is their felicity that is determined by context.

Given the many ways to convey an utterance, information structure can constrain speakers' choices in production -- at the level of word order (see 3-5), referring expression (see 6), and intonation (8-9). The IS constraint that appears over and over again is the generalization that new information is made salient by positioning it at the end of an utterance or by adding accent placement. Consider the voice alternation in (10-11) between active voice and passive voice.

(10) The dog chased a cat.

(11) The cat was chased by a dog.

The active-voice statement in (10) is a good answer in a context where someone has recently said "Remember that dog we saw yesterday who was chasing something? What did the dog chase?. What was the cat chased by?" For (10), the old information that's topical is "the dog chased X" and the statement in (10) provides the new focused information that "X = a cat". The passive-voice statement in (11) is a good answer in a context where someone has recently said "Remember that cat we saw yesterday who was being cased?, meaning that the old topical information is "the cat was chased by X". The statement in (11) provides the new information that "X = a dog". In both (10) and (11), the old information is ordered before the new information. Depending on the context, it is the active voice or the passive voice that can help achieve that ordering.

In this way, syntactic choices are influenced by pragmatic constraints and they can likewise signal the pragmatic status of entities in the larger discourse. In the active voice, the logical subject (the agent of the event) appears before the verb. The passive voice allows a promotion to syntactic subject of an entity that typically appears in a non-subject position (and demotion of the logical subject to a by-phrase). Both variants are grammatical, but context determines which is more felicitous. The constraint is that the syntactic subject must be at least as familiar within the discourse as the by-phrase noun phrase.

Psycholinguistic experiments have been used to test whether information structure influences processing. Beckman (1996) used a "got it" task in which participants needed to indicate after each sentence ifthey understood the sentence ('got it') by pressing "yes" or "no". The materials included items like (12) and (13) describing a transfer-of-possession event using a definite noun phrase and an indefinite for the Goal (umpire) and Theme (ball) thematic roles.

(12) The pitcher threw the umpire a ball.

(13) The pitcher threw an umpire the ball.

The Beckman study measured whole-sentence reaction times and a metalinguistic 'got it' decision. More recent work by Brown, Savova, and Gibson (2012) used self-paced reading to see how such effects unfold over time and are influenced by the surrounding discourse context. They compared passages in which the Goal or Theme referent was made topical (old) in a context sentence, and they varied the order of the referents in the prepositional order (PO) and dative order (DO). In (14-15), the old referent is underlined (though it was not underlined for the participants).

(14) Goal context: An understudy for a new Broadway show began conversing with a violinist who played in the orchestra.

a. PO/New-First: The understudy showed a notebook to the violinist as he explained his ideas.

b. DO/Given-First: The understudy showed the violinist a notebook as he explained his ideas.

(15)

Theme context: An understudy for a new Broadway show kept a notebook to document the show's progress.

a. PO/Given-First: The understudy showed the notebook to a violinist as he explained his ideas.

b. DO/New-First: The understudy showed a violinist the notebook as he explained his ideas.

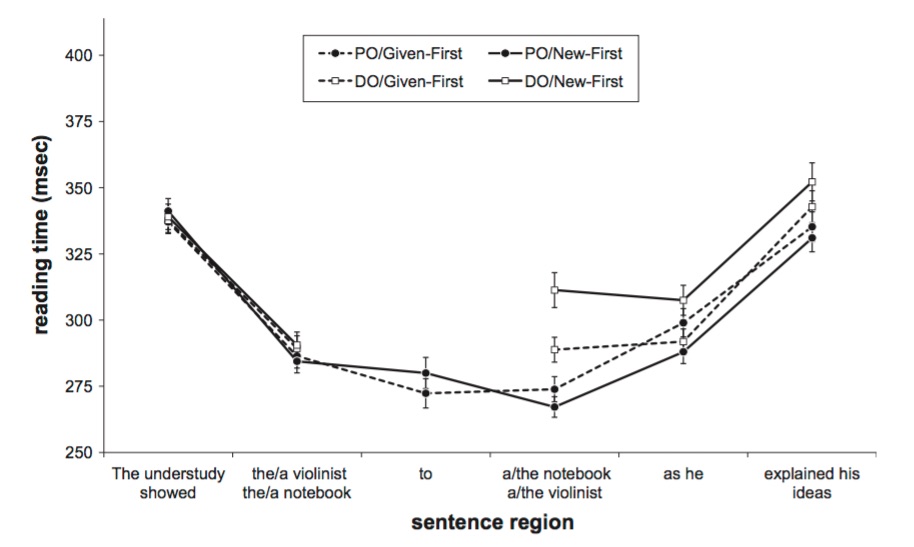

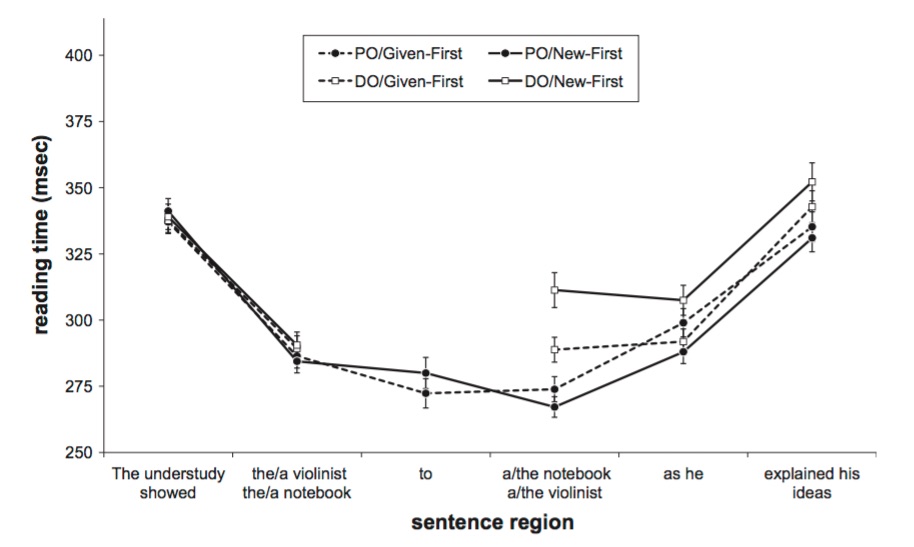

The question was whether old-before-new orderings of referents are preferred in both the PO and DO construction. The analysis therefore tests how reading times vary by information structure and syntactic structure. Brown et al.'s results are shown in the figure below.

The action is at the region where the second noun phrase appears. In that region, there is an interaction between syntactic structure and information structure. DO structures were read faster with the old-before-new ordering. For PO structures, the information status of the two referents mattered less, with marginally faster reading times for the new-before-old ordering.

Brown et al. interpreted these results to mean that information structure matters for some but not all syntactic representations. The representation of the DO structure, but not the PO structure, was characterised by an old-before-new constraint. Why might this be? One proposal is that the DO structure is the non-canonical variant of the more default PO structure. Non-canonical structures tend to be associated with stricter information structural constraints (see the active/passive examples above).

KEY POINTS: In felicitous discourse, the speaker connects what she says with the discourse up to that point and then adds something interesting that listeners didn't already know (be relevant and informative). Part of an utterance is old (relevant, linked to previous discourse) and part is new (informative). There is a preference for old before new.