To get started, consider the question below and try to think of contexts in which you are engaged in dialog (in person, on the phone) or in monologue (in a speech, in a lecture):

Researchers like Garrod & Pickering (2004) argue that certain properties of spoken language help make it easy (or easier). The common ground is central to their argument. For example, the building up of common ground makes decisions about what forms to use and anticipate easier. Speakers use particular words and constructions and their use requires the hearer to access those meanings and parse those structures, which is argued to have the effect of making those representations more accessible when it becomes the hearer's turn to be the speaker (sometimes called 'priming'). Even the questions that one speaker poses become the frames for constructing an answer: There's question~answer congruence between Where did John go to university? and He went to the University of Edinburgh. A dialog is the opposite of speaking in a vacuum, and in that sense, the speaker and hearer can share the responsibility of structuring the form and content of the discourse.

If common ground and priming and congruence are what make spoken language easy, what other kinds of alignment are there? There is evidence that speakers and hearers align easily in how they speak (accent, speech rate, clarity of articulation), in what linguistic forms they use (word choice, syntactic choice), and in other social elements (yawning, wincing, foot shaking, posture, tone of voice).

A classic study by Brennan & Clark (1996) tested alignment in reference. The question was whether speakers obey Gricean constraints on informativity (i.e., avoid overinformative expressions when a simpler expression will suffice) or whether they use the shared experience of talking together to dictate what expression is most appropriate (i.e., permit an overinformative expression if that expression is the one that has been used in the conversation up until now). In the study, participants were asked to play a card-sorting game, taking turns as the director (who described a set of objects on cards) and matcher (who sorted the cards).

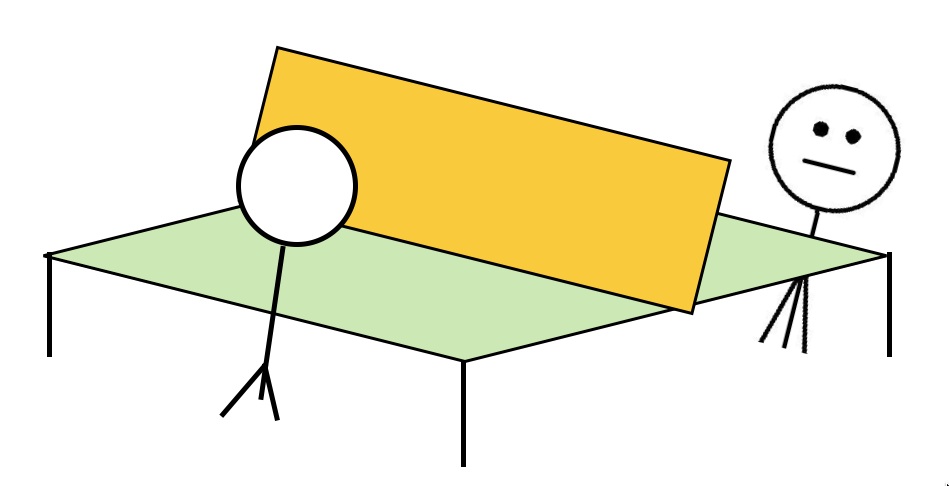

The task was designed to encourage participants to talk with their partner and the materials were set up so that a particular object appeared sometimes in a context where its base level description would suffice for disambiguation (e.g., "shoe" for the cards in (8)) and sometimes in a context where more detail was needed (e.g., the "brown shoe" or "loafer" in (9)).

(8) Card set A (unique shoe)

|

|

|

(9) Card set B (non-unique shoe)

|

|

|

If speakers obey the Quantity maxim, they should only use enough information to distinguish the referent from its surroundings. On the other hand, if they use partner-specific "entrained" names, they may need to use names which are longer than necessary for clarity. If informativity underlies reference choices, then speakers would be predicted to use more informative names when they switch to a context where the old name is not unique (if "shoe" unique in card set A, "loafer" in non-unique card set B). Likewise, speakers would be predicted to use less informative names when they switch back to a context where the more informative name is no longer required (if "loafer" in card set B, switch to "shoe" in a subsequent round with card set A). If informativity best predicts behaviour, then frequency (the number of times a director/matcher pair sort card set A or card set B) should not matter.

A Gricean model of reference would predict (i) you should be as informative as is required but (ii) not more informative than necessary. The results showed that for (i), yes, 77% of speakers produced "shoe" for card set A and 95% used a more informative expressin than "shoe" to describe the same image in card set B (the remaining 5% used "shoe" and matchers asked for more information). However, for (ii), no, when speakers returned to card set A after playing with card set B, they were found to maintain the more specific name ("loafer") 52% of the time. The results show that speakers override constraints on informativeness based on previous use. In addition, the degree of override reflects frequency of use.What can we conclude from Brennan & Clark's work (besides that you have to use goofy card-sorting games to get strangers to talk to each other in the lab)? First, there's the evidence that speakers use precedents even when doing so means being overinformative. Second, speakers rely on naming precedents more often the more firmly they are established. Third, there's a developmental point to be made (that the language we acquire is constantly in flux and being updated for each context) because names are provisional; even after a precedent has been firmly established, it can be changed or abandoned in the right context. Lastly, speakers establish conceptual pacts with listeners.

Why is this important? What impact does common ground have on speakers' and hearers' decisions? There are two important claims. One is that increased common ground allows for increased complexity. The other is that increased common ground allows for increased reduction.

To go on to section 7.3 "Audience design", click here.